This article aims to provide a clear, technically rigorous — yet practical — guide to gear pump displacement: what it means, how to calculate it, what the numbers tell you (and what they don’t), and what to watch out for when using displacement as a basis for pump selection or system design. Whether you are designing new equipment, replacing an existing pump, or verifying supplier data — this will be your go‑to reference for gear‑pump displacement.

What Is Gear Pump Displacement — Definitions & Concepts

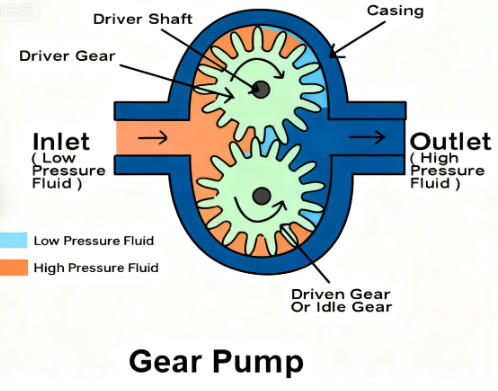

To begin with, a Gear pump is a classic “positive‑displacement” pump: it moves a fixed (or nearly fixed) volume of fluid for each revolution of its gears.

-

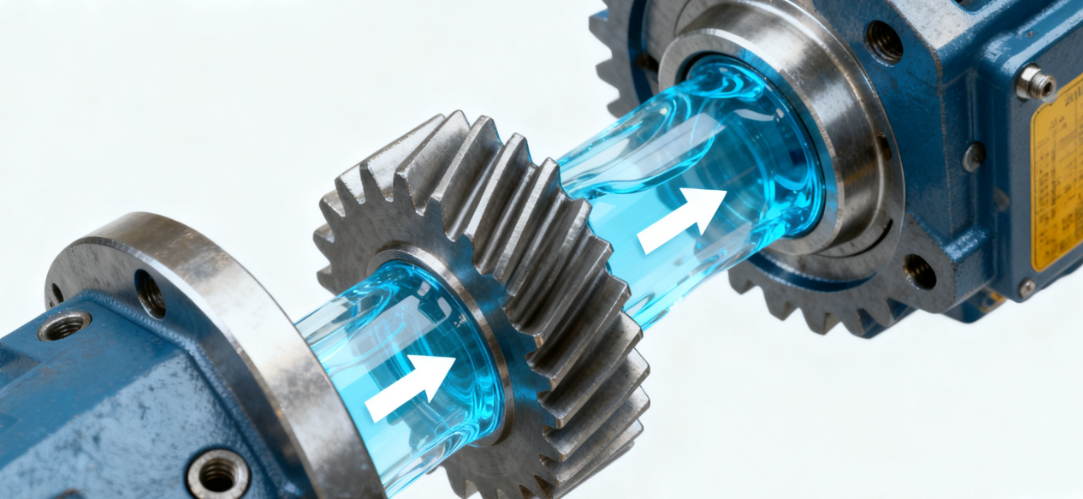

In typical external‑gear‑pump designs, two identical gears mesh side by side inside a close‑fitting housing; one is driven by the motor (“drive gear”), the other is the idler (“driven gear”).

-

As the gears rotate, on the inlet (suction) side the teeth separate, creating increasing volume between gear teeth and casing — fluid flows into this expanding chamber. On the discharge side, as the teeth mesh again, the volume shrinks, forcing the trapped fluid out through the outlet port.

-

Because the volume trapped between gear teeth (tooth‑space) is roughly constant per rotation, the pump delivers a nearly constant volume per revolution. Therefore, flow is (theoretically) directly proportional to rotational speed.

What “Displacement” Means

-

Theoretical (or nominal) displacement: the volume of fluid that the pump geometry can “displace” per single full revolution of the gears — under ideal conditions, assuming zero leakage. This is determined by the geometry: gear dimensions, spacing, and the volume between gear teeth. Many design/calculation formulas in external‑gear pumps are based on these geometric parameters.

-

Practical / actual output: real-world output generally differs from theoretical due to internal clearances, leakage (slip), volumetric losses, fluid viscosity, pressure conditions, wear, and other mechanical inefficiencies. As a result, actual volume delivered per revolution (and thus flow rate) is typically lower than nominal displacement × speed.

Displacement is therefore a foundational specification of a gear pump: it defines the potential volume per revolution, but must always be interpreted alongside other parameters (efficiency, losses, operating conditions) to understand real performance.

Common Formulas for Gear Pump Displacement Calculation

When we try to compute the displacement (volume per revolution) of an external gear pump, industry and academic sources provide several formulas — from relatively simple geometric approximations to more gear‑theory based forms. Below I present common formulas, variable definitions, and when you might use each.

Key Formulas

| Formula | Variables / Meaning | Notes / When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Vgp=π4×w×(Do2−Di2) | ww w = rotor (gear) width (e.g. in m or mm)

DoD_o D o = outer diameter (gear teeth tip circle) DiD_i D i = inner diameter (gear teeth root or base circle) |

This is a classic geometric formula for the theoretical volumetric displacement of an external gear pump. It computes the difference between the outer “cylinder” formed by gear tips and the inner “cylinder” formed by gear root — multiplied by width. It’s good for initial design or when gear‑dimensions are known. |

| Vgp≈6.66×z×m2×b | zz z = number of teeth on one gear

mm m = gear module (in mm) bb b = tooth width (in mm) |

A simplified / empirical approximation used in some pump‑manufacturing contexts. Useful when gear‑geometry is defined by standard gear parameters (module, tooth count, width), but exact root/outer diameters are not handy. |

| Variation: V=2π×K×z×m2×B×10−3 | KK K = a correction factor accounting for actual “tooth‑space volume vs ideal tooth‑volume” (depending on gear profile)

z,m,Bz, m, B z, m, B same as above (teeth count, module, tooth width) |

This formula is used when designers want a more realistic displacement estimation considering that actual “tooth‑space” is slightly more than ideal tooth volume. It’s more accurate than the rough 6.66‑based formula for many standard external gear pumps. |

Note on formula selection: Which formula you choose depends on what data you have (gear module vs actual gear diameters), required accuracy (rough estimate vs design-grade), and whether you need a quick ballpark number or a reliable spec for pump manufacturing / selection.

Example: Using the Geometric Formula

Suppose you have an external gear pump with:

-

rotor width w=25 mm(0.025 m)

-

gear outer diameter Do=80 mm(0.080 m)

-

gear inner/root diameter Di=60 mm(0.060 m)

Using the formula:

So the pump’s theoretical displacement would be about 55 cm³ per revolution.

If you know the pump speed (say 1500 rpm), you can then estimate theoretical flow:

Common Misconceptions & Pitfalls in Displacement Calculation / Interpretation

In our decades of experience at Poocca, we often encounter recurring misunderstandings among engineers, purchasers, and even experienced maintenance teams when they work with gear‑pump displacement. Misinterpreting displacement or ignoring real‑world factors can lead to serious mismatches between expected and actual performance. Here are the most common misconceptions — and why they can be costly mistakes.

Frequent Misconceptions (and Why They’re Dangerous)

-

Misconception: “Fixed displacement = fixed flow; gear pump cannot provide variable flow.”

→ Reality: While many gear pumps are fixed‑displacement, flow is only “fixed” if speed and load remain unchanged. By varying the drive speed (e.g. using a VFD), the flow can be modulated proportionally. Also, downstream flow‑control valves can adjust actual flow (though with efficiency/energy tradeoffs). -

Misconception: “Gear pump displacement listed in datasheet equals actual output flow: just plug in RPM and get flow.”

→ Reality: The nominal or theoretical displacement doesn’t account for internal leakage (“slip”), clearance losses, fluid viscosity effects, pressure, wear, etc. Actual flow is always somewhat lower than theoretical — often by a margin of 5 %–20 % or more, depending on conditions. -

Misconception: “Higher fluid viscosity always yields better performance for gear pumps.”

→ Reality: Higher viscosity does reduce leakage through clearances (improving volumetric efficiency), but overly viscous fluids increase friction, torque requirements, heating, and may cause suction or cavitation issues — especially at start‑up or under variable load. -

Misconception: “If gear‑to-housing clearance is very small at design, performance will stay high forever.”

→ Reality: Tight clearances at manufacture help, but wear over time (gear teeth, bearings, side plates) gradually increases clearances. Leakage (slip) then increases — leading to degraded volumetric efficiency, lower flow, more heat/noise, and more rapid wear. In some pumps, once clearance increases beyond a threshold, performance degrades quickly. -

Misconception: “Displacement formula based on gear geometry is precise enough for all gear pumps.”

→ Reality: Simple geometric or module‑based formulas assume ideal conditions — standard gear profile, perfect machining, no clearance losses, no leakage, no slip, standard fluid viscosity, no wear, and standard operating conditions. For real pumps (especially custom or heavy‑duty ones), these assumptions may not hold. Using formula alone without considering real‑world factors often over‑estimates capacity.

Conclusion

Accurately calculating the displacement of a gear pump — and using that information wisely — is a critical first step for correct pump selection, system design, or replacement specification. However, displacement alone is not a guarantee of actual performance. Theoretical calculations must always be paired with a realistic understanding of volumetric efficiency, leakage, fluid properties, pressure/temperature conditions, mechanical tolerances, and ongoing wear.

For engineers, OEMs, or maintenance managers: treat the displacement value as a baseline. Always design with margins — account for slip, losses, and worst‑case operating conditions. And plan periodic testing and maintenance to monitor actual flow/output over time and detect efficiency degradation early.

At Poocca, we recognize these complexities: we combine careful design, precise machining, and quality control to deliver gear pumps that meet nominal displacement specs while minimizing leakage and performance loss over time. When evaluating or specifying a gear pump, don’t just look at cc/rev — look at the full context: geometry, fluid, pressure, tolerance, maintenance. Only then you can ensure reliability, efficiency, and value.

Contact Poocca — Why and When to Reach Out

If you are designing or upgrading a hydraulic system — or considering replacing or specifying a gear pump — we at Poocca are ready to assist.

-

We can help you select or custom‑design a gear pump whose theoretical displacement, geometry, and tolerances match your system’s flow, pressure, fluid type, and duty cycle.

-

We provide detailed datasheets and performance curves, including expected volumetric efficiency, pressure‑vs‑flow behavior, and long‑term wear tolerance — not just “cc/rev” numbers.

-

For non‑standard requirements (e.g. high pressure, heavy oil or high‑viscosity fluid, aggressive duty cycles), we can adjust gear profile, clearances, sealing, and housing design to optimize real output and longevity.

-

We support after‑sales testing and commissioning — measuring actual flow, efficiency, and helping you tune system parameters (speed, oil viscosity, suction conditions) for best performance.

If you want a pump tailored to your needs — or help evaluating specs from a supplier — contact us at Poocca. We believe informed design and tight manufacturing tolerances make the difference between a “spec sheet number” and a reliable, efficient pump in real operation.

Post time: Nov-29-2025